Earlier today, I was sitting at my desk and slurping noodles when the thought crossed my mind, “These are good, but I could really go for some rice…”

Over the past 19 months, I have adapted to Indonesia and Java in many ways. Yet, there remain currents of social communication and expectations that are so inherently Javanese and so foreign to my American upbringing that I still sometimes stumble over where I fit in the grand scheme.

There is a sense of decorum inherent in Javanese culture. This includes treating your guest like royalty, avoiding conflict, and saving face. It also encompasses how people speak to one another. To really understand Javanese decorum, you have to look at the Javanese language itself.

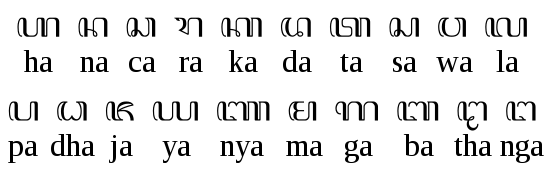

Javanese has multiple levels of politeness, and each level can have its very own vocabulary. This means that learning Javanese is almost like learning 3-5 different languages.

The three basic levels are…

Ngoko: used for close friends, peers, and those of a lower “status” relative to you (ex. younger siblings or children).

Madya: used for ‘in-between’ situations in which you don’t want to be too formal, too informal, or don’t the status of a stranger with whom you are speaking.

Krama: (pronounced “kromo”) used in formal situations or when showing respect to people of higher status (ex. parents, elders, officials, or when speaking in a formal setting).

For example…

Indonesians love to eat. If you wanted to eat, this is what you could say in Javanese.

Ngoko: Aku arep mangan.

Madya: Kulo ajeng nedha.

Krama: Kulo badhe nadhi. (or, if you want to be more humble, Dalem badhe nedhi.)

But then if you want to politely welcome your guest to eat, you wouldn’t use mangan, nedha, nadhi, or nedhi, but rather dhahar. As in Mongo, didhahar (“Please, eat.”)

So for one daily action, you have your choice of five different words.

I hope it is becoming clear to you at this point why I have been slow to learn Javanese.

Nevertheless, I have been struggling through the most basic of basics with my language tutor as she tries to drill into my brain the most menial of Ngoko and Krama sentences.

My tutor and me at Candi Ceto.

One week, with my list of Ngoko and Krama vocabulary spread before me, I wrote short descriptions of my family. My language tutor checked off my Krama paragraph fairly quickly, and moved on to Ngoko. I thought this would be a simple act of substitution – formal for informal – but as it turned out, the issue wasn’t quite so simple.

I had written a sentence about having one sibling: my older brother. Although I was writing as if I was talking to someone of equal or lower status to me, because I was referring to someone older – the first born of my family – I was still expected to use the formal Krama as a sign of respect.

Simply memorizing which vocabulary fits in which category, Ngoko or Krama, wasn’t enough – I also needed to develop an internal Javanese sense of where I was in relation to both the person I was talking to and the person I was talking about.

My futile attempts to learn Javanese – note the Indonesian to Ngoko to Krama translations. Too many words!

Life in a Javanese village tends to be intensely communal, and the Javanese language, in its very structure, is a constant reminder of where you fit in the societal puzzle – and that is something that is often difficult for me to figure out in Indonesia.

Raised in a land that aspires to equality and mobility, I believe fiercely that I am worthy of equal respect by the very virtue of being a human individual. In our frequent Star Wars action figure battles and Lego construction projects, I expected that my ideas and personal agency would be given as much consideration as my older brother’s (and my feelings of being deprived of these rights led to many a meltdown in my youth). This, for me, forms a large part of my identity.

Identity in much of Asia, and certainly on Java, however, is often formed based on where you see yourself (your past, your purpose, and your potential) in the social framework. It certainly doesn’t mean that Indonesians don’t believe in equality and mobility, but these concepts manifests themselves differently. Their ability to see themselves as fitting into a social slot – of knowing when to give and expect respect – is as inseparable from their personal identities as their mother language. It was, after all, their mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles, older siblings and neighbors, who taught them that language. And that, perhaps, does deserve some gratefulness and an added helping of respect.

In every culture, there is so much more going on than what we see on the surface. Often, we are unaware of what exactly makes us the way we are – why we communicate and behave towards others the way we do. Our identities are inextricably wound into history, climate, family, and society. But discovering the intricacies of the people and cultures around us, and thereby shedding light into our own, is what makes the world such an exciting place to explore.